Introduction by Dr. Bainard Cowan:

One of the signs of health in the current upswing of writing on Catholic themes is the efforts being made not simply to criticize contemporary culture but to resuscitate the imagination more directly. A dying or crumbling culture does not engage the human imagination; to the extent art still naturally tends to provide a “mirror of society,” it will only mirror back images of our own captivity.

This is a topic you should expect to hear with some frequency if you visit the Catholic Imagination Conference on our campus at the end of this month, where Jason Baxter, author of The Infinite Beauty of the World: Dante’s Encyclopedia and the Names of God and the recent The Medieval Mind of C. S. Lewis: How Great Books Shaped a Great Mind, will be one of the authors featured there.

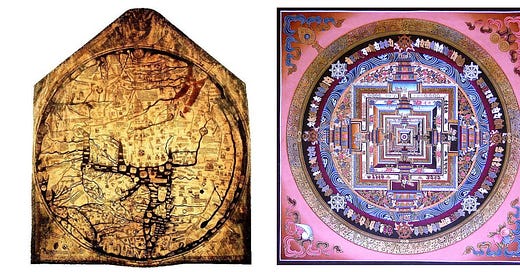

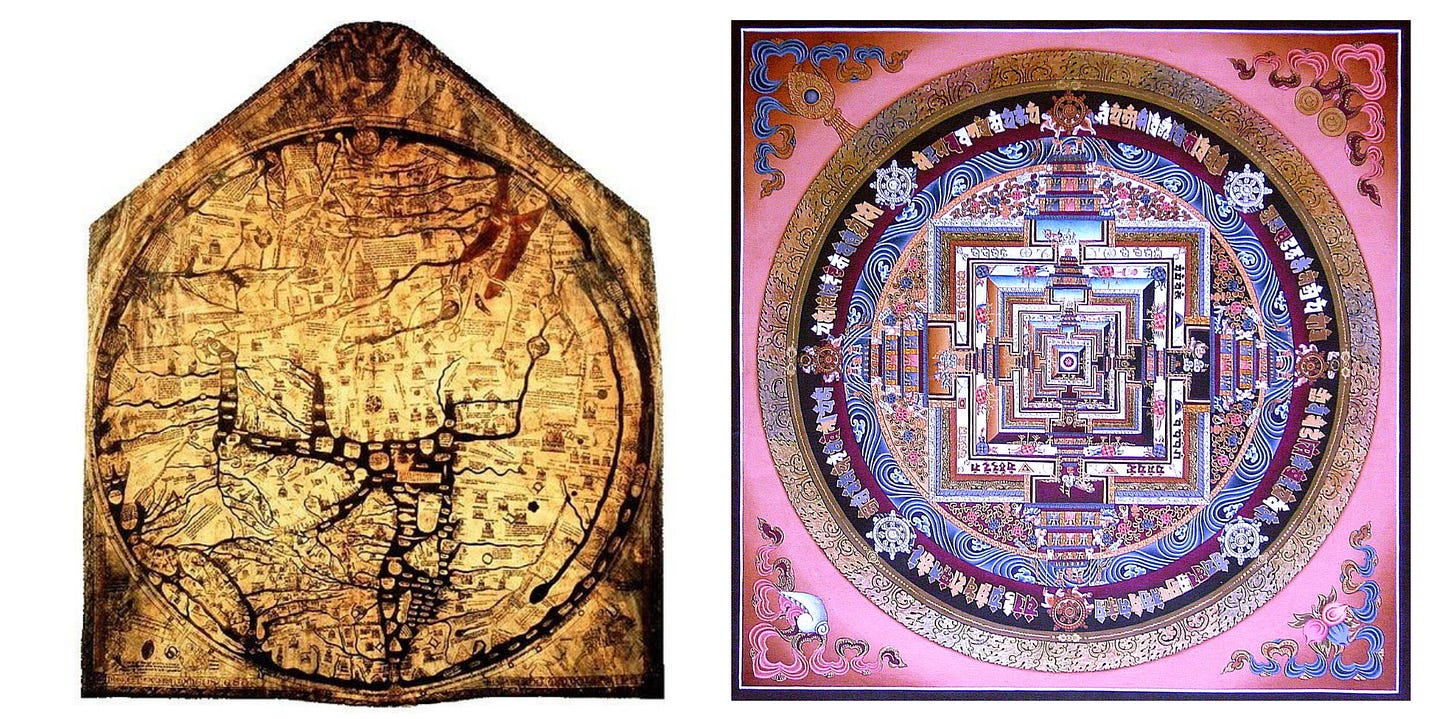

In “What Were Humans?,” our long-read essay featured in preparation for this conference, Jason Baxter’s tour of twelfth-century Neoplatonist writing summons readers’ dormant instinct for finding beauty in complexity, calling moderns once again to love the world, and finding analogues in Eastern art or wherever it may hide.

Baxter begins with a trenchant critique of the “flattening” that is at work constantly in contemporary media, adding a sense of urgency to the recovery of inwardness. But the urgency should not turn into a culture war, to be fought inevitably on the very field of battle that has already been flattened. The urgency is rather that those who are the consumers of the flattened media image--and that is virtually everyone today--recognize the trait of inwardness in the image when they witness it. For such recognition it waits, patiently, if only to be met and responded to by a real “human.”

Below is a preview of Jason Baxter’s article. Read the full piece here.

The Twentieth Century was the age of firebrands, revolutionaries, iconoclasts, and radicals, who publicly and violently proclaimed their desire to dismantle the old and liquify inherited social structures. In his 1909 “Futurist Manifesto,” Filippo Tomaso Marinetti put it in a particularly dramatic way: “We want to demolish museums and libraries…. Italy has been too long the great second-hand market. We want to get rid of the innumerable museums which cover it with innumerable cemeteries…. Heap up the fire to the shelves of the libraries! Divert the canals to flood the cellars of the museums!... Take the picks and hammers! Undermine the foundation of venerable towns!”[i] Marinetti’s manic call to burn libraries, flood museums, and chop up old buildings with picks and sledgehammers was a sentiment shared by writers whose heads were less addled by absinthe. Indeed, almost three centuries earlier, the High Priest of Modernity, René Descartes, in his Discourse on Method (1637), likened his own intellectual project to demolishing a historical house and replacing it with a new, rationally-built structure. And in the twentieth century, as Peter Galison has shown, there was a fascinating alliance forged between the most influential school of philosophy, the logical positivists, and the Bauhaus, a movement in industrial design and architecture. They came together to create what Galison calls “a new antiphilosophy… emphasizing…‘transparent construction,’ a manifest building up from simple elements to all higher forms that would, by virtue of the systematic constructional program itself, guarantee the exclusion of the decorative, mystical, or metaphysical. In other words, a glass house, which might now seem quaint to us, was, in its age, the perfect representative of a new approach to philosophy, society, and living: demolish the past, liberate ourselves from its restraints, and build up a new way of life based on “simple, accessible units.” Like the Bauhaus movement, the so-called Vienna Circle “conceived of itself as modern and scientific, as a movement that would tear apart the stagnant, pointless inquiry that called itself philosophy.” To replace traditional philosophy, “the Circle wanted to erect a unified structure of science in which all knowledge…would be built up from logical strings of basic experiential propositions.”[ii]

And so a disorganized array of free thinkers, politicians, writers, architects, intellectuals, and artists, like a group of stars that do not make up a constellation, set about to update, modernize, reboot, re-engineer, and rethink society, governance, sexuality, relationships between the sexes, education, and pretty much any organized activity that mattered. It was an exciting time, an aggressive time, a time which gendered itself masculine, in which manly men--and manly women--worked hard to demolish rickety structures, build a culture of speed, and create a society in which we live with machines as our neighbors. Italian futurists even dreamed of a time in which human beings would drink gasoline, so that they would become more like their neighbors. To my mind, the ambition of the age is summed up in a statue located in Dallas, the modern city par excellence. Outside of Love Field Airport stands an overlooked statue of Icarus, the mythological boy who flew too high and burned up his wings in the heat of the sun. Surely an inauspicious statue to plant outside of an airport, unless this time, you were going to do it right. But how ironic to borrow a Greek myth to mock the limitations of antiquity?

Read more here….

[i] Filippo Marinetti, “Futurist Manifesto,” in Futurist Manifestos, ed. Umbra Apollonio (Boston, MA: MFA Publications, 2001), 19-24 (22-23).

[ii] Peter Galison, “Aufbau/Bauhaus: Logical Positivism and Architectural Modernism,” Critical Inquiry 16:4 (1990), 709-710, 711, 713.

I am totally sympathetic to the spirit of Baxter’s eloquent defense of the life of the heart and mind and the value of our human classical heritage. But the panopticon, logical positivist scientism and the days of Marinetti are long gone, science has added a whole raft of ideas and fields that are not reductionist at all and indeed deeply in the exploratory and inventive spirit of nature itself. And the social media, enemy of any depth of thought, are just as hostile to science as any cultural conservative, as all the various forms of paranoid denial demonstrate. The horrors of the social media are not new: Dante found them all in the inferno before Galileo even existed. Real science may be part of the answer, not the problem. Gregor Mendel, father of modern genetics, and Georges Lemaitre, father of Big Bang theory, were both members of Catholic religious orders.